Shooting everything from underwater wildlife to Somalia’s famine victims, Peter “Hopper” Stone is best known for the still photography he does on major motion picture sets. How he became a shooter for the big studios is a tale he describes as “a long and winding road” from his hometown of Stamford, Connecticut.

With his mother and older brother involved in photography when he was a child, eventually Stone started making enough noise until rewarded with his own Minolta A5. A scholarship for a year in Rome gave him time to pursue learning the photojournalism ropes, after which he moved to Helsinki for five years. Then, it was on to Mexico City for almost three years, where he covered the North American Free Trade Agreement story.

At the start of his career, Stone was in his twenties and witnessed “the tail end of the golden age of photojournalism,” as he calls it. The news industry witnessed the fall of Eastern Europe, the U.S. invasion of Panama, the fall of the Soviet Union, the First Gulf War, the crisis in Somalia, and the disintegration of Yugoslavia, all in fairly short order. The expense of sending journalists to remote locations became prohibitive, and editors realized freelancers were heading to war zones on their own dime. Freelancers were abundant. “All they had to do was wait for the film to come across their desks,” Stone explains. “That was the decline of that kind of editorial business. You had to risk your life and some magazine would pay you for three days, plus local expenses. Now that’s over.”

During that time, Stone covered some of the cruelest and ugliest aspects of human behavior. He went to Somalia during a newspaper’s freelance-freeze because no staffers would agree go there. Stone makes clear the reason he went was not the adrenaline rush of getting shot at or navigating a road with land mines. “That’s not exciting. No one in their right mind wants to be excited by someone shooting at them. These locations are insanely interesting. You learn a lot both about the human condition, and about yourself,” he says. “You come away thinking what’s important and not important about you. It helps put things in perspective. 36 hours after leaving Somalia, I was back in Helsinki listening to my friends talk about their lives and problems they were having with the economy during that recession. I came away glad these were the problems we had, as opposed to the problems I had just come from. Shooting in a dangerous place like Somalia really helped me understand the world.”

In 1991 he joined Black Star, working internationally and for local press in Finland, where he worked as a newspaper photographer. In Mexico City as a Black Star stringer, he also did corporate work. “By 1996, I saw the future,” he says. “I had to argue for two days with a newspaper over a $25 expense. I didn’t want to hit middle age doing that. I found myself sitting in a movie theater and watching a film. As the credits rolled by, I saw the words ‘still photographer,” and I literally pointed at the screen and said, ‘I want that job.'”

Stone took three classes at what is now called Maine Media Workshops, where he studied Unit Still Photography with Kerry Hayes, who became his mentor. When the course was over, he bought a sound blimp and moved to Los Angeles. Eventually working his way into the coveted world behind the scenes of major film production, Stone discovered there were things he liked and didn’t like about working on different types of films. Action and comedy were quickly identified as his preferred assignments.

In short order, Stone came up with his own analysis of the work he did for his new movie studio clients. “I call it diet photojournalism,” he says. “Your job is to lay low, stay out of the way, not affect events, and capture the story.” The difference between working in Hollywood and his previous photojournalism is “they don’t shoot live ammunition at you, and no one’s going to attack you or beat you up. The worst thing that can happen to you is some actor or director will yell at you and ruin your day.”

Particularly within the genre of action films, Stone enjoys to work as second unit photographer, and did so on the first Spiderman film. “Second unit is where all the cool stuff happens,” he says. “All the stunts, all the explosions, all the big stuff. I was hooked. It’s a logistical challenge. They’re working on making this huge movie, and the still photographer is just supposed to get their shot. They might be shooting it with eight or ten cameras. You can’t be in the way. Sometimes you can’t even ask questions. If it’s a big explosion, they’re doing it just once.”

On comedy films, the operative word is “fun.” Stone likes working with the actors on those films. Equally at home working on dramas, which he finds slightly more demanding. Stone doesn’t like encroaching on delicate scenes as they play out. “When there’s a crying scene or a heavy dramatic moment, the last place I want to be is in that room. They don’t want me there, and savvy photo editors will tell you not to bother.”

Stone has become an expert at the psychological negotiations necessary for moving in and out of a film set, navigating explosive directors, moody actors, and crew attempting to assert their small spheres of influence. “You need to find out who you play well with,” he says, laughing. “You work hard to get the shots which have been requested, but you don’t want to be pushy. There’s a lot of moving to different locations in order to avoid personality conflicts. Everyone’s there to make a movie, and there’s tremendous financial pressure to get everything done on time. I’ve become very good at making myself unobtrusive.”

Recently, Stone has been branching out with cinematography. He’s using HDSLR’s and working on expanding his reel with shorts, spots, and promos. After attending last year’s Collision Conference in Los Angeles, which centered on the merging of stills and motion, he saw the industry changes already taking place. “It’s coming whether we like it or not,” he says. “Between the Red One and the Canon EOS 5D Mark II, this is what’s happening now. Still photographers have to adapt.”

Awash in camera bodies, a Nikon shooter for fifteen years, Stone is currently shooting the Canon 1D Mark IV. “I’m one of the very fortunate few who got his hands on one of them in January,” he says. He brings a wide range of lenses and a sound blimp to jobs on movie sets. Although he doesn’t use them on movie jobs, he owns and shoots a Mamiya RZ and a Mamiya 7.

“I’ve got a Sekonic L-758DR,” says Stone. “When used with the target, it’s a magic, bullet-proof light meter. I always knew the back of your camera is not the greatest reference, including the histogram. It’s horrible. I’ve got three profiles for the three main cameras I use. They can be off by as much as half of a stop. That’s why I rely on the 758. There’s no more guesswork. I tell cinematographers about this device all the time.”

Stone uses PocketWizards on-set often. When large stunts or pyrotechnics are being performed, he often uses them on multiple remote cameras to get as much coverage as possible.

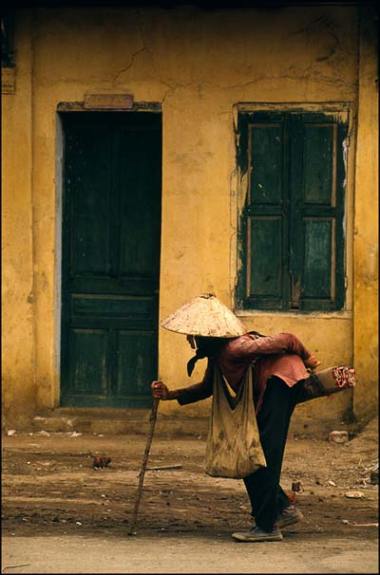

Stone’s moniker — the one most people know him by — was given to him on the set of Three Seasons, the first American film shot in Vietnam after relations with that country began to normalize after the war. “I showed up on the set with long red hair,” recalls Stone, laughing. “I had a scarf around my head, a couple of earrings, and five cameras around my neck. People said, ‘You look like Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now!’ There were already three people named Peter on the crew. I never liked my own name, and I was hoping a better name would come around. I kept it.”

Although the desire to travel to exotic locations and shoot stories still has a certain amount of interest for Stone, he understands and accepts the reality of the market for photos. “The unfortunate truth is when the majority of producers are looking through a photographer’s work to decide if they will hire you for a film, they’d rather see a mediocre photo of Tom Hanks on a filmset than a great photo of a real person they don’t know taken in the real world,” Stone explains. When he was once showing his book to get a job on an action film, the producer came across a journalism photo. “What movie was that from?” the producer asked. Stone replied, “that wasn’t a movie. That was the war in Yugoslavia.” The producer shrugged his shoulders and turned the page. “I guess it wasn’t action-filled enough for him,” Stone says between laughs.

Peter Hopper Stone Photography

Written by Ron Egatz

You must be logged in to post a comment.