Robert Gerhardt came to photography in a way few do. As a Sociology major with a concentration in Anthropology at the College of the Holy Cross, Gerhardt was not the typical art school photography student. Encouraged by his anthropology advisor, he took a photography course so he’d be able to document things during field research.

“Harold Feinstein, a student of W. Eugene Smith, was my first photo teacher, and within ten minutes of the first class when he was showing us his photographs, I was hooked,” Gerhardt explains. He soon came to realize he could write endlessly about sociology and anthropology, “but a photograph says so much more than any writing can ever really do.”

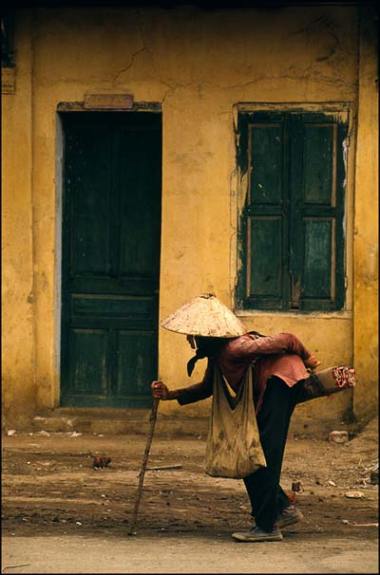

©Robert Gerhardt

Gerhardt went on to receive an M.F.A. in Photography from the Art Institute of Boston at Lesley University. Working both between degrees and after his M.F.A., Gerhardt has worked at several major museums, photographing art work, which paid bills and continues to enable him to explore his true photographic love, street shooting.

Just as it’s not often you see a full-time photographer coming out of Sociology and Anthropology majors, it’s not often you see a substantial photographic project get kicked off because of a quote from a Henry Miller novel. The long passage, which is from Tropic of Capricorn, begins “But I saw a street called Myrtle Avenue, which runs from Borough Hall to Fresh Pond Road, and down this street no saint ever walked….” The passage inspired a project now in its third year, and almost didn’t happen. “I had just gotten Tropic of Capricorn out of the library on a whim, and I was looking for whatever my next project was going to be. I came across that passage,” Gerhardt explains. “It made me think, ‘I’ve got to check this place out.'”

Since Miller published the novel in 1938, areas of Myrtle Avenue have been both been changed and time has seemingly stood still. As any competent sociologist or anthropologist would, Gerhardt is chronicling what he’s found, often with brutal honesty. “Parts of it are drastically different [from the novel] and parts of it you think would never have changed,” he reports. “It goes from Hipsterville Central down by Fort Greene through some really bad parts, Bed‑Stuy and Bushwick, and that sort of picks up again once you get back to Ridgewood and Queens.”

What has remained unchanged for Gerhardt is his constant companion, his Sekonic L-508 meter. “It’s seven or eight years old. I always have it on me,” he says. “It’s always in my bag. As the light changes during the day—shade versus sun and all that kind of stuff—you sort of have to. I mean, you can use meters in cameras, but they’re never as good. For shooting, especially the building exteriors and stuff like that, you want to know what the range is. It’s very easy and quick to use, which I like. That spot meter function, is above and beyond I think, the greatest feature of it.”

While his day job consists of shooting in the studio all day, for his own work, Gerhardt is always moving and adapting to changing light conditions of the street. Typically shooting with black and white film, he is also working on a project shot in color on Manhattan’s 42nd Street and Times Square area. Many of the photos in this series are shot surreptitiously. “I do shoot from the hip a lot, mainly because I don’t want to disturb people. I try to shoot it unknown for the most part,” he says. For all his personal film work, he relies on just a few cameras. Previously he was shooting Leica M6s, but he now has a pair of Nikon F3s. He primarily shoots Ilford film, and prints on their paper, doing his own darkroom work.

©Robert Gerhardt

Another major project Gerhardt has undertaken has been his work documenting the Mae Tao Clinic, which offers free medical care to refugees and others crossing the border from Burma to Thailand. The things he saw and the images he captured changed his view of the world. “The first person I met when at the clinic, other than my translator, was a 24-year-old woman who and lost both of her legs to a landmine,” he recalls. “You meet somebody like that and you’re like, ‘this is a completely different world than where I’m coming from.'” Upon returning home, Gerhardt sent them CDs of all the images he shot.

Currently, Gerhardt has a show at Johnson State College in Johnson, Vermont until December 20th. On October 27th, he’ll be doing an artist lecture there, as well. His show will also travel to South Carolina in November and December. Syracuse, New York and Dayton, Ohio will have it in January and February. Next year’s dates also include the University of St. Francis in Fort Wayne, Indiana next fall.

In another documentary photography project, The Straphangers, Gerhardt shot in New York City subways for three years. During that time, even in post-September 11 New York, only one person spoke to him about his photography. It seems the disinterest of New York Subway riders was the perfect environment for Gerhardt to document essentially unseen. What remains is a series of images where virtually no subjects make eye contact with the lens. Workers are crammed into subway cars, each looking in different directions, each in their own world, yet pressed toe to toe. There are diverse faces which comprise the city, and their isolation stands in direct contrast to the density of the place they’ve chosen to live their lives. Gerhardt examines this unflinchingly. He has given us nothing less than an updating of Robert Frank’s vision of America.

©Robert Gerhardt

For his most recent project, Gerhardt has chosen to document a mosque and community center in Brooklyn, New York run by the Muslim American Society. He was given permission to photograph the mosque and meetings in an old catering hall after reading about their struggle to convert an old convent on Staten Island into a Muslim community center. These images remind us the United States is comprised mostly of immigrants and their descendants. He has photos of signs about Ramadan written in a schoolgirl’s careful hand, a young daughter in a hijab at prayers with her father, and a Muslim man in a plaid shirt with an American flag pin on the pocket. The photographs are moody, and his use of available light suits the subject matter perfectly: people continuing traditions of their ancestors in an unsure time.

In much of the body of photographic work Gerhardt has presented, he documents a United States unlike the one we were raised to believe in. Streets are devoid of traffic, restaurants are torn down, abandoned homes sit on the edge of woods, parks stand without grass, flags hang forlornly. Unfulfilled potential is an underlying message in much of his work’s subject matter.

©Robert Gerhardt

Rarely shooting in direct sunlight, Gerhardt’s platinum skies and grainy shading are apropos aesthetics for the psychology he is attempting to produce in each image. He meters and exposes his shots carefully, rarely accenting any particular part of his frames. The result of this approach tells us this is the way the world is, nothing is worthy enough on its own for attention, and almost everything is chaotic. He truly is a sociologist and anthropologist visually documenting these quirky humans found at the beginning of the 21st Century.

Written by Ron Egatz

You must be logged in to post a comment.